Drunk Stoned Brilliant Immortal

It’s fair to say that most people – even those who came of age during the late 1960s and 1970s — probably have no idea how influential National Lampoon magazine was (and still is) to American comedy. Douglas Tirola’s entertaining new documentary Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead is a sort of primer for anyone who equates the Lampoon name mainly with a disparate assortment of increasingly juvenile movies.

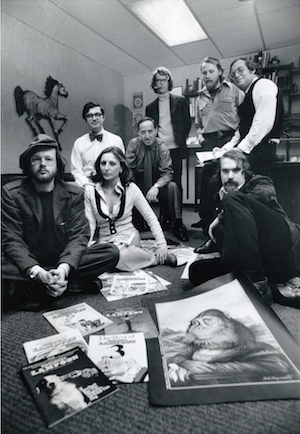

The fast-paced film uses lively animation and tons of vintage graphics, including iconic magazine covers, to illustrate the publication’s history, told via snippets of interviews with those who were involved with the magazine firsthand (Anne Beatts, P.J. O’Rourke) or consider it crucial to their development, comedic and otherwise (Judd Apatow, John Goodman, Billy Bob Thornton). The main focus is (understandably) National Lampoon’s heyday, from birth in the late 1960s through decline in the 1980s, with emphasis on the various characters who shaped it, especially founding editors Doug Kenney and Henry Beard, and chairman/CEO Matty Simmons.

In the mid-1960s, the satirical student-run Harvard Lampoon (first published in 1876) fell under the stewardship of charismatic, unstable Kenney and serious, organized Beard, the dynamic duo who would go on to co-found National Lampoon in 1970. Among the film’s many enlightening bits of information is the fact that a popular parody of Mademoiselle magazine was responsible for broadening the college Lampoon’s subscription base, enabling its expansion well beyond Cambridge. The national magazine’s first official hire was the legendarily volatile Michael O’Donoghue, who brought a dark, angry tone to the publication and would later become an integral part of early Saturday Night Live.

The film follows the magazine’s growing popularity, fueled by Kenney and Beard’s refusal to bow to criticism or squeamish advertisers. National Lampoon’s content was often crass, shocking, raunchy and incredibly sexist (though the latter was par for the course in those days), the result of a largely drug- and alcohol-fueled staff who were encouraged to push any and all boundaries. “It’s the job of a satirist to make people in power really uncomfortable,” explains key contributor Tony Hendra of the publication’s tendency to outrage. Beatts was one of the few women allowed into this bad boys club, mainly because she was dating one of the writers. (She’d go on to write the infamous ad parody showing a floating VW Beetle with the tagline, “If Ted Kennedy drove a Volkswagen, he’d be President today.” Volkswagen sued.) There were illustrations from greats including Gahan Wilson and Charles Rodrigues, plus headline-grabbing covers like the renowned “If you don’t buy this magazine, we’ll shoot this dog” issue from 1973. Once advertisers were persuaded to take advantage of the mag’s young, hip demographic, NL flourished economically as well as creatively, at one point becoming the second most popular magazine on newsstands.

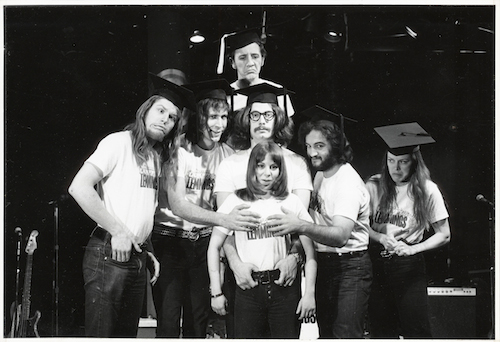

Soon came a hit comedy LP, O’Donoghue and Hendra’s Radio Dinner, which grew out of O’Donoghue’s National Lampoon Radio Hour, which itself began featuring young Second City actors Gilda Radner, Bill Murray, Harold Ramis and John Belushi, among others. Then came the hit Off-Broadway comedy show National Lampoon Lemmings, starring Chevy Chase, Belushi, and Christopher Guest, which included a musical parody of Woodstock. It’s a kick seeing youthful versions of these now seasoned (or deceased) comedy pros, especially Belushi unleashing his Joe Cocker imitation for the first time. The cast’s shaggy, devil-may-care abandon is palpable, especially in these days of over-curated, well-groomed entertainment. Lemmings would be the forerunner of Saturday Night Live, which, according to one commentator, was responsible for sucking the life out of the magazine, as the NL brand of subversive humor became available to wider audiences.

The film charts both the publication’s decline and that of Kenney, whose self-destruction is mourned by his friend Chase. We see the birth of National Lampoon movies, including early blockbuster Animal House, which would become the blueprint for Hollywood college-humor flicks for decades to come; and National Lampoon Vacation, based on a John Hughes short story, which would spawn many sequels. (Another interesting tidbit: Hughes wrote some of the dirtiest stuff in the mag.) But the film doesn’t really delve into the movie franchise and its many spinoffs, sticking mainly to the magazine, which officially ceased publication in 1998, long after it ceased being relevant.

Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead is an eye-opening look at what now seems a distant era in publishing and media in general. Hendra likens National Lampoon‘s heyday to Paris in the ’20s for writers. Though things were far from idyllic, given the instability and huge egos involved, it’s hard not to feel nostalgic for a time when anything seemed possible in comedy and entertainment in general.

Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead is playing at the IFC Center in Manhattan.

—Marina Zogbi