- 3 years ago

-

French filmmaker Bruno Dumont has never played by any movie-making rules, which has resulted in a fascinating career of provocative and unsettling work, most of which can be classed as art films. A former philosophy professor, Dumont has clearly relished exploring themes of good and evil, incorporating gritty realism, extreme violence and sexuality (La Vie de Jesus, Twentynine Palms), as well as unexpected humor (the charmingly offbeat P’tit Quinquin).

Dumont’s latest, France, starring Léa Seydoux as the title character, is slicker looking than previous efforts, which makes it more confounding in some ways. A satirical exploration of celebrity and television journalism, France is uneven in tone, veering from wildly unsubtle to inscrutable, its deliberate pace elongating scenes that sometimes seem like they should be more revelatory.

It’s also quite watchable, thanks mainly to Seydoux, who plays France de Meurs, a famous Parisian TV journalist who hosts a talk show. Early in the film, she is recognized and besieged for autographs on the street, which she seems to enjoy. Dumont digitally inserts France into footage of an actual press conference with President Emmanuel Macron, where she asks a tough question and mocks the event via a series of silent but expressive exchanges with her assistant Lou (comedian Blanche Gardin). Lou, a near slapstick character, fawns over her boss and treats TV journalism like a fame game.

In one drawn-out scene, France takes charge during the shoot of a segment about jihadists in Africa, posing soldiers like game pieces and reshooting what appear to be candid conversations, laughing with her photographer. Yet, she also seems genuinely concerned about the plight of the region and people. This dichotomy of real vs. fake (scenes, emotions) is echoed throughout the film.

When France accidentally drives into and injures a bike messenger, she begins spiraling into some kind of existential crisis about both her celebrity and her need for it. She begins visiting him in the hospital and at his home, offering money to his immigrant parents, who are thrilled by her attention. All of this is covered in the tabloids.

Meanwhile, things aren’t going so well at her house (a claustrophobic museum-like apartment), with a frustrated writer husband (Benjamin Biolay) and alienated young son; though it’s never exactly clear what the marital problems are, aside from France receiving a much heftier paycheck.

France starts breaking down on set and decides to leave the TV world, checking into a luxurious spa in the Alps, where she embarks on what seems like a Hallmark romance with a fellow patient. After a major betrayal on his part, she is back on TV with a big news story about African migrants into which she embeds herself by boarding their raft (and again completely directing the action). While prepping the clip for her show, her flippant conversations with Lou are accidentally aired. Though this would seem catastrophic, it’s not really, according to Lou, who assures France that “People will hate you, then they’ll love you even more than before; that’s how TV works.”

There’s so much going on in the film, including France’s changing mental state, as we watch various emotions—mostly sorrow—play on her face, that it becomes exhausting rather than moving, which may be the point. (Seydoux spends much of the film crying and puffy-eyed, yet still looking beautiful; this is part of the satire, we assume.) A horrible tragedy occurs late in the film, after which France interviews the wife of a child murderer. Again, she is both professionally detached and overcome with emotion.

France is a strange drama; what’s being mocked is clear, yet it’s too tonally uneven to be completely satisfying (it might be easier going for those living in France; some nuances and references are undoubtedly lost on the rest of us). There is mournful music by late French composer Christophe throughout, which adds a melancholy vibe to the film.

A star vehicle for Seydoux, France certainly offers a lot for her fans to savor. With scenes both unexpected and overly predictable, it is not a film that one can ease into comfortably, but it offers an interesting perspective into celebrity journalism and the contradictions surrounding it.

France opens this Friday, December 10, at Film at Lincoln Center in New York.

—Marina Zogbi

Latest News

- 3 years ago

-

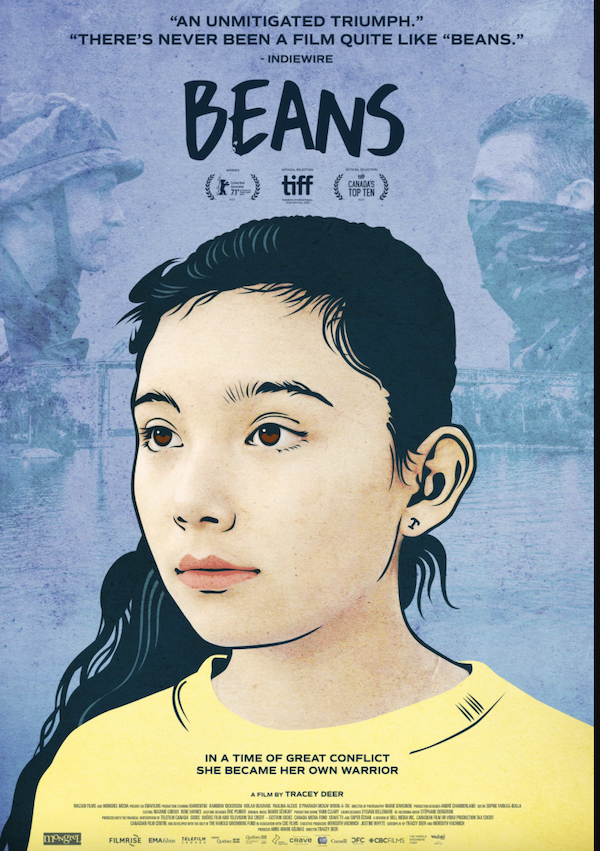

Inspired by true events, Tracey Deer’s Beans is a powerful and impassioned coming-of-age story set amid a recent violent chapter of Canadian history.

The 1990 Oka Crisis was a land dispute between the Mohawk community and the mostly white government of Oka, Quebec, over plans for a sacred burial ground to be turned into a golf course. An intense 78-day confrontation ensued, some of which is included in the film via archival footage. Deer, a Mohawk who was inspired by her own memories of the time, instills her film with scenes and emotions that are both tender and tough, which makes for a particularly engaging experience.

At the start of the film, smart, sensitive 12-year-old Tekahentakwa, nicknamed Beans (beautifully portrayed by Kiawentiio) and her mom Lily (Rainbow Dickerson, also excellent) travel from their home on the Kahnawá:ke Mohawk Reserve to apply to a fancy school in town. (In an uncomfortable moment, the white administrator tries repeatedly and unsuccessfully to pronounce “Tekahentakwa.”) Beans’ father is against the whole idea, but Lily is adamant that their daughter pursue an excellent education. The family is rounded out by young Ruby (Violah Beauvais), Beans’ frequent companion and a classic little sister sidekick.

Dad becomes involved in the protests against the golf course supporters, which soon becomes a standoff: In retaliation for the Mohawks’ blockade of a bridge that connects the community with Montreal, local authorities cut off the reserve from supplies, including food.

When Lily takes girls into town by boat to buy food, an ugly scene plays out in the supermarket. There are several scenes of hateful white bigotry, which have a crushing effect on Beans and escalate the film’s tension. The animosity against the Mohawks is palpable, underscored by interview clips from actual news reports of the time. In return, some of the Mohawk men curse and threaten anyone attempting to cross the bridge. Real footage of the confrontation is interspersed throughout, with testimony from people on both sides (sometimes in French). Apparently, we in the States don’t have a monopoly on North American bigotry.

At first, Beans tries to keep the situation at bay psychologically, pretending with Ruby that they’re eating ice cream and other treats instead of oatmeal. Eventually she seeks out a tough older local, April (Paulina Alexis), under whose tutelage she shops for trendy clothes and learns to fight. She practices cursing in the mirror, before doing it in real life. Her boldness is admired by April’s brother Hank and soon there is young (too young, in Beans’ case) romance afoot.

Meanwhile, we can’t help but worry about her transformation into an angry, unthinking girl; we know that this can have terrible consequences for the rest of a young person’s life, especially someone in her position.

Also worrisome is the escalating conflict, despite efforts on the part of the tribe’s women try to diffuse tense confrontations. Some of the reserve’s women and children go “on vacation” to a motel to get out of the hot spot. April and Hank are there too, however, and in a bid to impress, Beans starts a fight and completely loses control. Poor pregnant Lily (the true badass of the movie) takes the kids home. Again, suspense builds as they meet obstacles on the way.

After confronted with an unreasonable demand by Hank (to put it mildly), Beans is left feeling completely alone.

Though situations both large and personal eventually get resolved, it was sure tough getting there. And despite a few scenes that are reminiscent of typical adolescent angst (mainly involving interactions with tough kids), this is not a typical film about a young girl’s rebellious coming of age. The film’s pointed POV, raw emotion and rough situations make it memorable and powerful, as do the performances of Kiawentiio and Dickerson. It’s impossible to watch Beans without feeling a wealth of emotions, which is pretty great in itself.

Beans opens in select theaters and On Demand this Friday, November 5.

—Marina Zogbi

- 4 years ago

-

Courtesy of Music Box Films The subject of Sebastien Lifshitz’s sweet, sad documentary Little Girl, 8-year-old Sasha lives in rural France with her parents and siblings. We first see her carefully trying on various items of clothing and accessories, a popular pastime for most kids, but especially important to her.

Early in the film, we witness a conversation in which Sasha’s mother, Karine, tells a local doctor that at the age of two, her son insisted, “When I grow up I’ll be a girl,” and has never wavered from that certainty. The doctor asks Karine if she wished for a girl during her pregnancy, as if this might explain Sasha’s gender identification (!). Distraught, Karine admits that she did hope for a girl and that she has felt guilty ever since.

Thus begins Lifshitz’s poignant, pointed film. Shot in verité style without narration or identifying captions, Little Girl documents through conversations, interviews and fly-on-the-wall footage the struggles of a tirelessly devoted mother who wants nothing more than happiness and a semblance of normal childhood for her sensitive, intelligent child. Unfortunately, it’s a steep uphill battle for Karine, Sasha, and the rest of the family.

Courtesy of Music Box Films Karine takes Sasha to a sympathetic psychologist in Paris, who assures her that the desire for a girl during pregnancy has nothing to do with Sasha’s gender identification, and that there are many children like her. Sasha, who stoically admits that “Second grade teachers aren’t very nice,” is not only rejected by both boys and girls at school, but by teachers who can’t accept her for who she is. During the appointment, she cries silent tears, but can’t explain why. It’s clear that school is a very painful subject.

Also quite poignant are scenes of Sasha in dance class where the other girls get to wear pretty costumes while she’s given a boy’s tunic. Here, as elsewhere, the visuals are underscored by delicately lyrical music that seems to comment on Sasha’s vulnerability.

Scenes of happy home life show that at least Sasha has a supportive family going for her. We’re reminded that trans kids who are rejected by their parents get very little comfort indeed. Sasha’s father seems just as caring as his wife, and her older sister is a self-appointed protector. At one point, Karine’s level-headed young son advises, “Don’t take it from idiots,” referring to the administrators and teachers at Sasha’s school who are seemingly indifferent to her needs.

Courtesy of Music Box Films Finally, as third grade begins, things start to look up as Sasha is finally allowed to be who she is (though the dance studio is another story). Despite upbeat scenes of Sasha going to school in a skirt, her hair in a ponytail, the struggle for acceptance clearly doesn’t end here. Having fought hard for this victory, the exhausted Karine now worries about what may be in store for her daughter during adolescence. The future is clearly complicated.

A delicate, straightforward film that presents the trans experience from a new perspective, Little Girl is both lovely and heartbreaking.

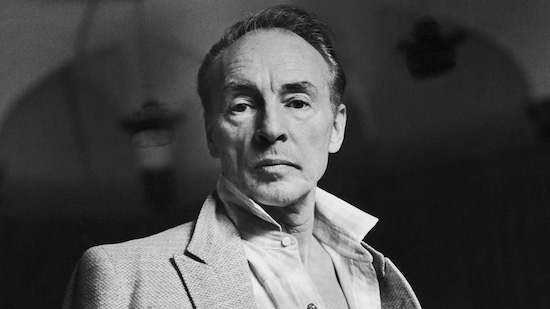

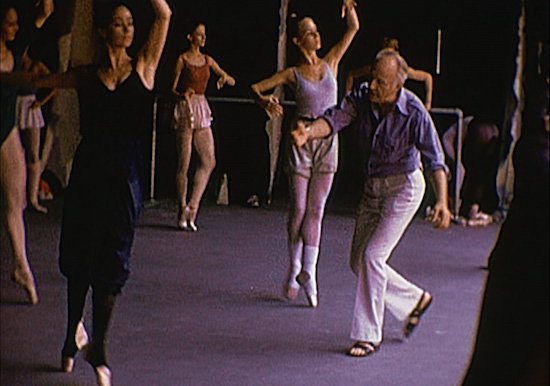

George Balanchine, In Balanchine’s Classroom

Photo: Ernst HassFor fans of George Balanchine and New York City Ballet, the company he founded and helmed until his death in 1983, In Balanchine’s Classroom is a welcome treat. In addition to archival footage of classes, rehearsals and performances, director Connie Hochman includes interviews with several of his most renowned dancers, including Merrill Ashley, the late Jacques D’Amboise, Heather Watts, Edward Villella and Gloria Govrin. Their deeply personal recollections of Balanchine’s unique philosophy and demanding technique—as well as their own insecurities, physical struggles and eventual success—provide fascinating insight into the man’s genius and the uniqueness of City Ballet. Anyone who’s ever seen a performance by Merrill Ashley, one of the most precise, fleet-footed of dancers, may be surprised to learn that she struggled mightily when she first joined the company, as did Villella and Watts. Eventually, they all became paradigms of Balanchine’s exciting, idiosyncratic style.

Jacques d’Amboise, In Balanchine’s Classroom

Courtesy of Zeitgeist FilmsThrough interviews and footage, we learn how Balanchine left Russia during the Revolution, later immigrating to the U.S., where he founded the School of American Ballet to teach his fresh, insanely fast choreography, pioneering a cool, new style considered by many to be quintessentially American. We also see how he pushed his dancers to move “bigger and faster” until they literally dropped to the floor. As Ashley notes, “Sometimes it seemed like he was being perverse.” Was it ethical to use these young bodies as experiments to test physical limits? Probably not. Did it result in some of the most astonishing choreography even seen in ballet? Absolutely.

There’s great footage of Balanchine teaching class in the 1970s, trying to convey the vision in his head by exhorting his confused dancers to “run starting forever.” Though exacting in many ways, he often kept dancers’ mistakes in the choreography because he liked the way they looked, or changed his steps to suit certain dancers’ bodies or strengths. He saw possibilities in unlikely dancers like the solid, towering Govrin, who says that she would not have stood a chance in another ballet company.

Courtesy of Zeitgeist Films Apparently, even today’s dancers—ostensibly faster and stronger than those of yesteryear—still find Balanchine’s style tricky and exhausting. The film features scenes of American Ballet Theatre principal Stella Abrera grappling with the intricacies of the fiendish Symphony in C as she’s coached by Ashley. Balanchine’s spirit and vision is clearly alive in the bodies and minds of his former dancers, several of whom regularly stage his ballets and are shown teaching various classes and companies.

An homage to a great artist, the film doesn’t get too deeply into the stickier aspects of Balanchine’s legacy, such as his habit of marrying his favorite dancers and discouraging others from getting married in general. (His all-time muse Suzanne Farrell, who left the company after marrying another dancer, only to return years later, isn’t interviewed for this film).

Though there is mention of pain, injury and sacrifice, among those featured in this film, dancing for Balanchine was a tremendous gift. We’re left wondering who will pass the torch of his genius when they are no longer around.

Little Girl and In Balanchine’s Classroom open at Film Forum on Friday, September 17.

—Marina Zogbi

- 4 years ago

-

The Macaluso Sisters, courtesy of Glass Half Full Media Many of us are familiar with the horrific 2014 attacks by Islamic State fighters (ISIS) on the Yazidi Kurdish minority in northern Iraq, from various news stories. Especially reprehensible were the forced “marriages” of Yazidi girls and young women to ISIS soldiers, who basically used them as sex slaves. Now, MTV Documentary Films brings us right into that incomprehensible world with Sabaya (a term loosely translated as “sex slave”), a riveting documentary by Kurdish/Swedish director Hogir Hirori.

Guarded by Kurdish forces, 73,000 ISIS supporters are held in the Al-Hol Camp in Syria, along with many of the Yazidi women and girls they have abducted. Many of these women—several of whom witnessed their families being murdered by their captors—were taken in their early teens and have spent their entire adolescence enslaved. Sabaya follows an incredibly intrepid and determined group of volunteer Yazidis who repeatedly risk their lives trying to rescue as many women and girls as possible from Al-Hol, considered the most dangerous camp in the Middle East.

Sabaya, Courtesy of MTV Documentary Films Mahmud and Ziyad of the Yazidi Home Center lead the rescue group, whose mission it is to bring the girls back home to their families, or whatever is left of them. Constantly monitoring their phones and almost as often losing cell service, the two men patiently plot nighttime raids on the camp, armed with guns and information from female infiltrators, many of whom are former sabaya.

We ride along and witness the tense search of myriad mazelike tents, as the group look for specific girls they know are being held there. Often they come up empty, as the girls have been moved, though there is a lot of forceful denial from the women who have been tasked with watching over the sabaya; their lives are undoubtedly in danger as well. The volunteer group are sometimes followed and shot at by ISIS supporters; it’s clear that they could easily be killed for their actions.

Courtesy of MTV Documentary Films When they do manage to rescue a girl, she is often traumatized, as in the case of Leila, who talks about suicide. Another girl, Mitra, now seven, was only a year old when she was taken from her home. The girls are cared for by Mahmud’s wife and mother, and they connect with other young women who have suffered the same fate. Once they have amassed enough rescuees, the tireless Mahmud and Ziyad drive them home to Sinjar in northern Iraq, where they are exchanged for a group of former sabaya, who are then trained to infiltrate the camp.

The rescued girls of Sabaya, in their t-shirts and skinny jeans, are typical teens in many ways, a reminder that atrocities against girls and women everywhere occur far too easily and frequently. Though 206 Yazidi girls and women had been rescued from ISIS at the time the film was made, over 2,000 were still missing.

Sabaya is currently playing at Film Forum in Manhattan and other theaters.

The Macaluso Sisters, Emma Dante’s film adaptation of her play of the same name, is a haunting, beautifully shot drama that builds to a poignant and graceful ending. The story of five orphaned sisters in working-class Palermo, Sicily, and the tragedy that shapes their lives, is shown in three time frames, beginning when the siblings are around 5 to 20 years old. (Twelve different actors portray the sisters at various stages). Surprisingly, the narrative doesn’t seem to have lost any of its power in its transition from stage to film. That is certainly a testament to Dante’s skill in translating what could have been an unwieldy work.

The sisters—wiry, responsible Maria, who longs to be a ballet dancer; tempestuous, make-up loving Pinuccia; odd, literature-obsessed Lia; chubby, fun-loving Katia, and the precocious youngest, Antonella—live in a rambling, old apartment in Palermo, where they keep doves and pigeons on the roof, renting them out for weddings and other events. Though life seems chaotic and there’s a fair amount of familial bickering, the sisters clearly share a strong bond. The apartment’s dark, cluttered rooms are contrasted with the doves’ sunny rooftop aerie, which also functions as a playroom for the sisters.

One day, the girls make an excursion to Charleston Beach, a busy city facility with an old-fashioned pavilion, where they splash happily in the water and lead a bunch of other kids in a dance on the water’s edge. While Maria meets a friend with whom she shares a delirious kiss, there is a catastrophe we don’t quite see. The film then jumps ahead several years to middle age, when the married Katia visits the house to attend a dinner arranged by Maria, who still lives there with Pinuccia and Lia. It soon becomes apparent how the tragedy of that day has affected them all. There is much arguing, a physical altercation, and a terrible announcement. As in the first act, Dante pauses the action every once in a while to present melancholy stills of various rooms in the house; even without their occupants, the rooms resonate with the lives lived there.

Several other repeated motifs throughout—broken plates, birds flying overhead, as well as recurring interactions between sisters, even when they’re not physically present—give the film a lyrical, poetic quality.

By the last act, as the house is emptied out, we keenly feel the end of the sisters’ saga and the inevitable push of time itself. Messy, moving, raw and lovely, The Macaluso Sisters is an unusual and unusually resonant film.

The Macaluso Sisters opens in theaters beginning Friday, August. 6.

—Marina Zogbi

- 4 years ago

-

Courtesy of Music Box Films The 19th feature from acclaimed French filmmaker François Ozon, Summer of 85 is based on Aidan Chambers’ 1982 novel Dance on my Grave, one of the first Young Adult books published by a major house to depict homosexuality. For many teens (including Ozon, apparently), it was a hugely influential part of adolescence. A beautifully shot film (the French seaside setting plays a big role), Summer of 85 feels like a throwback to that decade: colorful, dramatic, and a little obvious. That tone, however, might mainly be due to the POV of its protagonist, a 16-year-old in the throes of love.

Alexis (Felix Lefebvre)—or Alex, as he has begun calling himself)—a cherubic blonde teen who is casually obsessed with death, has recently moved to a seaside town in Normandy where his father is a dockworker. One day he takes out a friend’s boat and capsizes, only to be saved by a slightly older, much savvier teen, David (the perfectly cast Benjamin Voisin). Early in the film, Alex refers to this angular, charismatic stranger as a “future corpse,” so we know upfront that David is doomed. In a flash-forward, we see Alex being interviewed about his role in some unnamed crime, ostensibly related to David’s demise.

Courtesy of Music Box Films After the boating incident, David takes Alex under his well-muscled wing, bringing him home to meet his widowed mother (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi) who makes him undress and take a hot bath. She’s uncomfortably flirtatious, but her neediness is somewhat mitigated by the fact that she seems genuinely thrilled that her son has a new friend. After his father’s death, she explains, David ran wild, but is now “back,” thanks to Alex. The boys’ relationship evolves quickly into something deeper as Alex becomes increasingly enthralled with the reckless, cocky David.

Meanwhile, the film continues to toggle back and forth between past and present, where Alex’s no-nonsense caseworker (Aurore Broutin) futilely asks for details of his relationship with David so that she can present his case to the judge. She eventually meets with Alex’s French teacher (Melvil Poupaud) who encouraged the boy to write down his story. There is a stark contrast between the happily infatuated Alex of the not so distant past (though intense, the relationship lasted only six weeks), and the sullen, dulled version who is being questioned. Slowly the mystery unravels, with several more jumps back and forth in time.

Of course, Alex and David’s relationship could not last, especially after English au pair Kate (Philippine Velge) shows up on the scene. There is jealousy and emotional devastation for Alex, followed by tragedy. Afterward, he becomes even more obsessed with David, which seems far-fetched, except that it is happening to a 16-year-old.

Courtesy of Music Box Films In addition to the striped and pastel-colored clothes and tiered haircuts of the time, Summer of 85 includes an appropriate soundtrack (The Cure, Bananarama) with the exception of Rod Stewart’s mid-’70s version of “Sailing.” The song underscores two important scenes in the movie, one inside a dance club and a climactic final scene. Though seemingly out of step with the film’s other time-perfect details, it pulls the narrative out of a nostalgic haze into a kind of timelessness.

As for the uncomplicated narrative and somewhat cliched dialogue, Ozon has clearly chosen to mirror his character’s POV completely, a somewhat risky approach, as the film can seem a bit shallow. A fitting movie for Pride Month, Summer of 85 will resonate more with some than others, though its theme of youthful infatuation is universal.

Summer of 85 opens on Friday, June 18, at select theaters including the Angelika Film Center and the Village East in NYC.

—Marina Zogbi