A True Shooting Star

Matthew Miele and Justin Bare’s documentary Harry Benson: Shoot First is an entertaining, at times astonishing, look at the career of a man who is responsible for countless iconic images from the past 50 years. In addition to a dizzying succession of photographic images, the film includes an array of testimonials from famous contemporaries and subjects in addition to family members, plus droll commentary from the 86-year-old Benson himself. Dan Rather, Carl Bernstein and Bryant Gumbel are among the journalists who weigh in on Benson and his work; Sharon Stone, Joe Namath, and (sigh) Donald J. Trump, among others, contribute anecdotes about their own experiences with the venerable photographer.

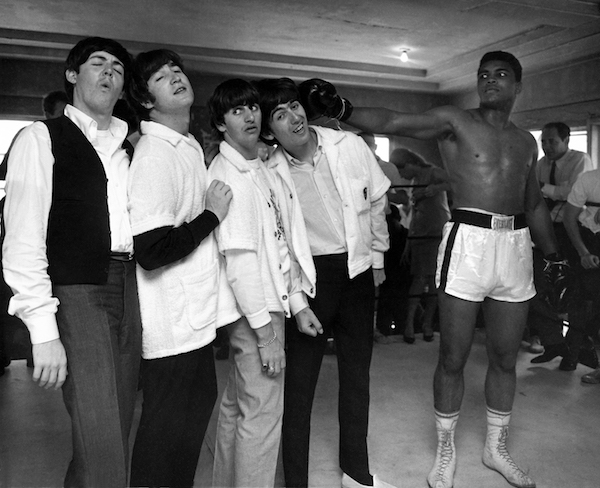

One of the film’s striking motifs is Benson’s uncanny ability to be in the “right” place at the “right” time, whether in Memphis when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated or on a beach when the famously camera-shy Greta Garbo was taking a swim. Another running theme is how the charming Scot befriended almost everyone he shot, a diverse group including Muhammad Ali, Richard Nixon, and Mark David Chapman. His talent and tenacity resulted in a huge collection of photographs unmatched in their immediacy and intimacy, from shocking images of a dying Bobby Kennedy to dreamy photos of reclusive chess champion Bobby Fischer nuzzling a white horse.

Though mainly known for shooting celebrities and political figures, Benson also traveled to places like Mogadishu, Somalia, and the West Bank, capturing war- and poverty-torn locales and their inhabitants with an unflinching eye. As the film makes clear, he never stopped to consider whether or not to take a picture, no matter how sensitive the subject. Thus the film’s title and his reputation among some as a ruthless competitor.

Early on, the film documents what Benson is still best known for: dynamic black and white shots of the Beatles taken when he accompanied the fledgling band to the U.S. in 1964. These playful pictures were the first images many people saw of the Fab Four. They, like many to come, trusted Benson, who–like all good photographers of people–was able to break down his subjects’ guard, often uncovering something truthful.

The documentary juxtaposes Benson’s often provocative shots of celebs with his somber studies of Civil Rights era marches and riots. (He also managed to get disturbing close-ups of KKK members and rallies.) The photographer seemingly threw himself into the midst of the action, no matter how dangerous; his journalistic instincts were honed early in his career in the dog-eat-dog world of Fleet Street, where he worked for the Daily Express. Later his photo essays for Life magazine would shape how people experienced the big (and often tragic) news of the day.

Benson was covering Robert Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign, so he was at L.A.’s Ambassador Hotel when the senator was assassinated. He automatically began taking pictures, including one of an anguished Ethel holding up her hand. Of course those pictures are iconic now, but some, like Carl Bernstein, wonder about ethics. “That’s an excuse that photographers use when they can’t get the shot,” says Benson dismissively. Clearly not everyone loved his methods. Garbo’s nephew wonders why the photographer persisted in shooting the aging actress, resulting in a picture she hated.

Much to the frustration of his fellow photographers, Benson was renowned for his ability to capture scenarios previously thought impossible, including Michael Jackson’s bedroom at Neverland Ranch and Joe Namath’s bachelor pad at the height of the quarterback’s playboy heyday. He aced difficult assignments, including a devastated President Nixon on the day of his resignation and a bald Elizabeth Taylor in the hospital after brain surgery.

Late in the film we get a glimpse of Benson’s humble beginnings when he goes back to his hometown outside of Glasgow and meets up with a childhood friend. Here the photographer talks about his “rough and tumble” childhood, and having to leave school at 13 to work as a delivery boy because his grades were so poor. Photography got him out of a hopeless-seeming situation. (At 86, however, he still retains the scrappy attitude of his youth.)

Despite its fast pace, dazzling parade of celebrity stills and largely amusing recollections, Harry Benson: Shoot First ultimately winds up being more than just a fabulous eyeful. It’s a veritable timeline of recent history captured through the lens of a remarkable talent who never hesitated to take his shot. As he points out: “A great photograph can never happen again.”

Harry Benson: Shoot First opens Friday at the IFC Center, with simultaneous release through On Demand, Amazon, and iTunes.

—Marina Zogbi